We Need More Black Swans: Building Diversity And Racial Equality In Ballet

A ballet blanc, which literally translates to “white ballet,” is a 19th century romantic style which reveres white sylphs, swans, and ghost-like figures called ‘wilis.’ La Sylphide, Swan Lake, and Giselle are examples of this. Ballet companies pride themselves on performing these iconic productions with impeccable coordination and symmetry of their corps de ballet (the members of a ballet company who dance together as a group).

Dancers of Les Grands Ballets Canadiens de Montréal

Though the image of ballerinas all in white tutus seems harmless, the lack of progress in racial diversity on stage becomes quickly apparent when the desire for sameness bleeds beyond ballet technique, creating the expectation that all dancers should have the same hair, same skin color, and same body type. In an Instagram post, Felipe Domingos, a dancer with the Finnish National Ballet, relates how he was taken out of a ballet purely because of his skin color. The choreographer told him that the dance required uniformity and that his appearance drew too much attention.

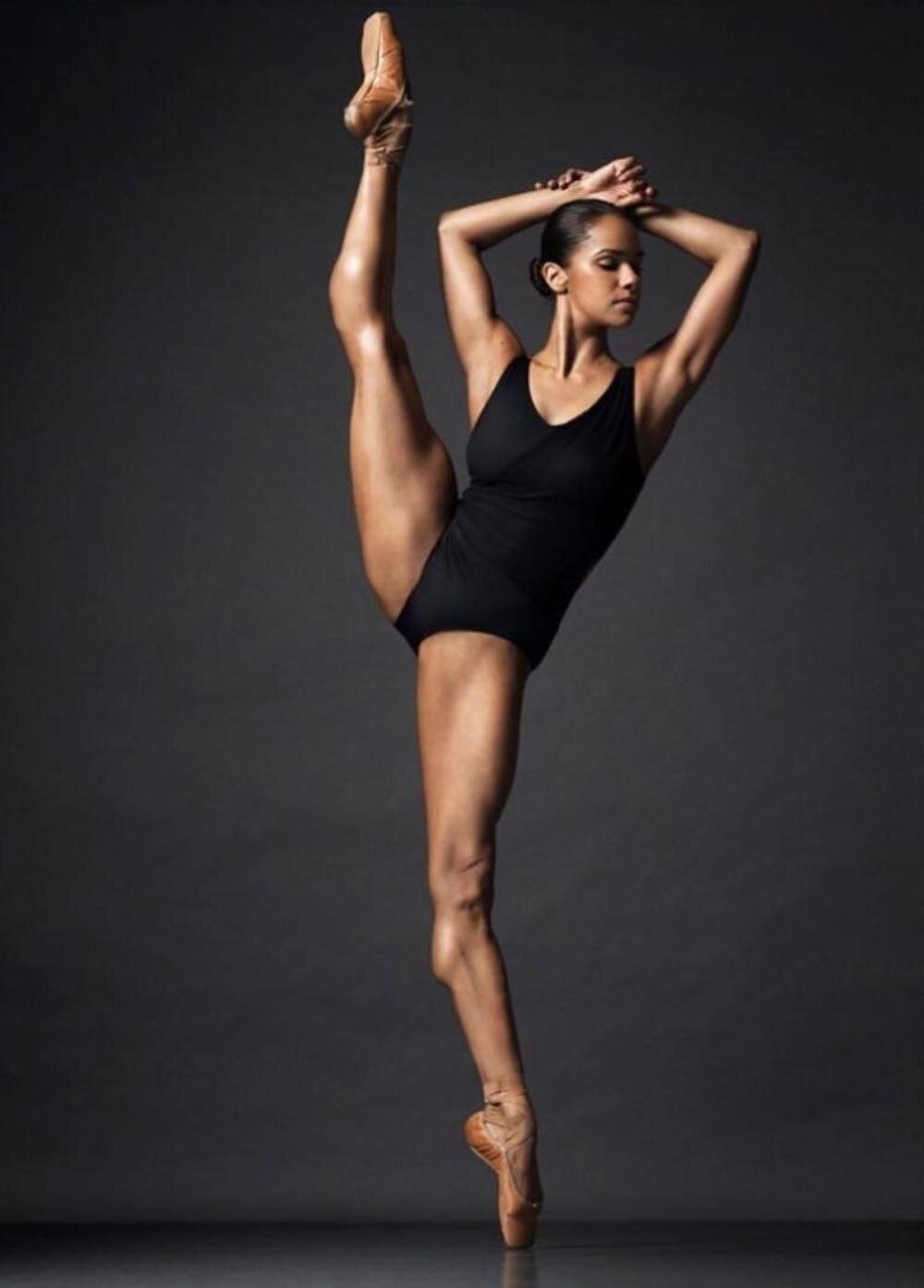

Misty Copeland photographed by Henry Leutwyler.

Sadly, there are far too many stories like this. In an interview with TIME, ballet icon Misty Copeland, who made history as the first African American woman to be promoted to principal dancer at American Ballet Theatre (ABT), recounts being told to lighten her skin with makeup to fit in with the rest of the company. Another ABT dancer of color, Gabe Stone Shayer, describes his experience with racism in ballet in Dance Magazine. He trained at the Bolshoi Ballet Academy in Moscow, Russia, calling it a place “where political correctness does not get in the way of progress [in dance training].” He details racial stereotypes in casting, writing: “In one instance, a woman who had watched me perform a variation from Coppélia for a competition asked me if I would consider dancing Ali instead (the slave variation from Le Corsaire), insinuating that it would be a better fit.” These stories only graze the surface. While the Black Lives Matter movement is gaining more support, dancers have taken to social media to share their encounters with racism in ballet, demanding much-needed change.

Last year, Copeland reposted an Instagram photo of two white female ballet dancers in black body paint rehearsing for a Bolshoi production of La Bayadère. Copeland said, “It is painful to think about the fact that many prominent ballet companies refuse to hire dancers of color and instead opt to use blackface." In response, director of the Bolshoi Theater, Vladimir Urin told Russia's RIA Novosti news agency: "The ballet La Bayadère has been performed thousands of times in this production in Russia and abroad, and the Bolshoi Theatre will not get involved in such a discussion.” To this day, ballet’s euro-centric productions which date back over one-hundred years sometimes perpetuate a narrative that associates Blackness solely with slavery. With traditionalism often comes outdated, offensive themes, which can only begin to change by engaging in constructive conversations regarding racial sensitivity, diversity, and inclusion.

Racial equity in classical dance isn’t as simple as putting an end to blackface on stage. And racism in ballet isn’t always so glaring. Take the pointe shoe, an iconic symbol of the ballerina. These shiny satin slippers which allow ballerinas to float across the stage on their toes are almost always sold in a pale pink “flesh” tone. When performing without tights, dancers with black/brown skin tones are required to take extra time to “pancake” their slippers with makeup or dye in order to have shoes that match their skin. Only recently have pointe shoe brands such as Freed, Bloch, Capezio, Grishko, and Suffolk announced plans to start manufacturing shades to match darker complexions.

Freed of London & Ballet Black Collaboration. Photograph: Tyrone Singleton.

Real change in ballet doesn’t start after one conversation or adding more pointe shoe shades. It requires a systemic shift to embracing black bodies and letting go of the notion that all ballerinas should look the same. Famed New York City Ballet dancer Suzanne Farrell described the ideal ballerina as, “Leggy, linear, musical, unsentimental, elegant, and, of course, untouchably beautiful.” Even today, decades after Farrell’s time with NYCB, industry purists cling to this rigid aesthetic with dear life, often conflating a waif-like physique with the ability to dance gracefully. Consequently, this creates a problematic paradigm where many Black dancers are castigated as too “powerful,” “muscular,” and “curvy.”

Misty Copeland has used her fame as a platform to spark conversations about racial representation in ballet. She isn’t the only one, however. Michaela DePrince, who is now a soloist for the Dutch National Ballet, grew up an orphan in Sierra Leone. She was inspired by a magazine cover of a ballerina in a pink tutu. Deprince details her journey to become a world-famous dancer in her memoir Taking Flight: From War Orphan to Star Ballerina. Precious Adams, First Artist at English National Ballet, was criticized for not wearing pink tights on stage. She instead wears brown tights to match her skin tone. While there are far too few Black dancers in major classical companies, dancers of color such as Copeland, DePrince, and Adams are shining examples of 21st-century ballerinas.

Copeland, who took her first ballet class on a basketball court at the Boys & Girls Club, inspired American Ballet Theatre’s Project Plié. This is ABT’s initiative to expand racial and ethnic diversity in classical ballet by partnering with the Boys & Girls Club of America to offer workshops that identify gifted children and connect them with world-class training.

Tearsheet By Emily McKenzie.

In order for the art form to survive, ballet must continue to attract younger generations and reflect their diverse communities. With access to training opportunities, more children of color may discover they love the art form. Hopefully, ballet will evolve so that all dancers, regardless of race or ethnicity, feel welcome in studios so they can see a future on stage.

Article by Adele Cardani, Contributor, PhotoBook Magazine